The Hyge

The thing of it was, they each thought they hugged too well to quit. It was as if they had an aesthetic obligation to continue, like a talented artist or a brilliant mind.

Sometimes Robert put his arms around Jill’s waist and she wrapped hers about his neck. Sometimes they crossed arms, each placing one over a shoulder and one around ribs. Occasionally they did it all wrong, he up she down, like slow dancing on the opposite sides.

No matter how their arms went, their bodies fit together. They liked one another. Each lived alone and the warmth and pressure felt good.

The thing of it was, though, they did quit. They got in a tussle.

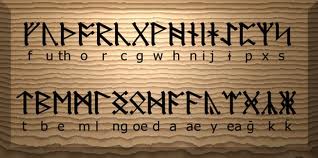

We can imagine them having sex if we wish. There’s a pungent Anglo Saxon word for that. We can picture another night, in Robert’s car, when they park and talk about Deborah’s death, when Robert tells Jill about the tumor emerging through Deborah’s skin, and the last time they tried, unsuccessfully, to make love, while Robert and Jill hold hands lightly, and both their tears fall on them. We can even picture those emotions leading them to form the two-backed beast, but there wouldn’t be much to write about. Jill wanted a stronger mate and Robert was not highly sexed.

Or we can imagine them refraining. Hugging with firmness and attempts at comfort after Robert’s narration of his wife’s last days, but with neither the timing nor the inertia-conquering impulse to advance beyond the boundaries of that hug. Jill just didn’t feel motivated to make the first move. Another description of Robert is sexually retarded.

Either way, it was only three months later that they had the little skirmish that led to estrangement. Robert was into his new phone and became so frustrated when he tried to demonstrate its features to Jill that he spoke carelessly to her, four times. Jill advised him to screw himself, and he took umbrage. She didn’t apologize.

A short time later, Jill heard that Robert was suffering from some cognitive infirmities. Memory and mood disorders beyond his years. She had noticed he was misplacing nouns when he forgot the word “usher” in her presence, but she attributed that to normal aging. She didn’t appreciate the extent of his failure till a mutual friend reported the diagnosis: acute progressive aphasia. Eloquent Robert was losing language. She heard that his mood was always confused or frustrated now, so she sensed it was worse than words. Surely his condition accounted for the way they had clashed. And it just as surely barred any reconciliation.